IAQ IQ, Spring 2016

©2016 Jeffrey C. May

What can make a “sick home” sick?

A number of years ago, I prepared a study of 600 “sick” homes (SHs) that I had investigated, and compared some characteristics of these homes to a randomly selected group of 300 “control” homes (CHs) that I had looked at as pre-purchase home inspections for home buyers.

I found some interesting consistencies in the 600 SHs as compared to the 300 CHs.

37% of the SHs had central A/C as compared to only 19% of the CHs.

41% of the SHs had hot-air heat as compared to only 29% of the CHs.

44% of the SH’s had finished and/or carpeted basements as compared to only 31% of the CHs.

These comparisons led me to conclude that in homes in which there are hot-air heat and finished basements with carpets, occupants were more likely to suffer health symptoms due to poor IAQ.

And central A/C was almost twice as likely to be present in SHs as compared to CHs!

My sampling results pointed to mold exposure as a major culprit. In 81% of the SHs, I found elevated levels of airborne fungal spores. Correspondingly, a majority of the A/C systems in SHs were contaminated with mold growth – most often on or near cooling coils.

It’s important to note, though, that occupants bore and continue to bear a chunk of the responsibility for the mold growth in their homes. It comes down to a lack of understanding of some basic scientific and building principals.

A simple thing like burning jar candles can result in soot depositions on walls and ceilings – wherever air flows are more turbulent due to temperature differentials (for example, above baseboard heating convectors and ceiling light fixtures, or where nails are attached to drywall). Soot particles stain wall and ceiling surfaces, but they are also unhealthy to inhale.

Many people use fragranced cleaning products. These may smell pleasant to some people, but are irritating to others. Fragrances are chemicals, after all; why add more chemicals to the indoor environment? These chemicals can be carried on airflows through a building – just as cooking odors can be carried from the kitchen into other parts of the house.

One man who owned a commercial building called me because one of his tenants – a lawyer – was complaining about an irritating odor that developed every other Friday afternoon from 2:00 to 3:00 p.m. in the foyer outside his offices. The lawyer was withholding his rent and threatening to break his lease. It ended up that the people who occupied the neighboring suite of offices hired a cleaner who came every other Friday afternoon and who used fragranced cleaning products. The cleaner switched to un-fragranced cleaning products, and the problem was solved.

Wood-burning stoves can create IAQ problems in unexpected ways. In one rental property, the two tenants sued the landlord to get out of their lease because the house contained extensive mold growth. They also wanted the landlord to pay for replacement for all their possessions, which they said were mold contaminated.

The landlord told me that the house contained a wood-burning stove. I suggested that he compare the heating bills for the winter the tenants had occupied the house to the bills a former tenant had paid for two previous winters.

The heating bills were extraordinarily low, and it hadn’t been that warm a winter. When the landlord questioned them about it, the tenants told him with some pride that they hadn’t used the central heating system much during the one winter they had occupied the house. They had depended instead on the wood-burning stove.

The tenants had kept a large pot of water on the stove to keep the air in the house moist. All that moisture was evaporating into the air, and then condensing on cold surfaces – and believe me, with minimal central heat, there were a lot of cold surfaces in this house!

As air cools, its relative humidity (RH) rises, and certain species of mold can grow when the RH is over 80%.

The tenants may have saved some money on oil, but they were faced with the expense of cleaning or even replacing their possessions. And conceivably, the landlord could go after them to cover the mold remediation work that was now required in the property.

Whether tenants or property owners, most occupants don’t know much about their homes’ mechanical systems.

People don’t have adequate filtration (a pleated-media filter with at least a MERV-8 rating but preferably with a MERV-11 rating) in their A/C systems, and they don’t change the filters that they do have often enough. They don’t check to be sure the filter holder slots are airtight. Manufacturers of electronic filters recommend only quarterly cleaning of the equipment, whereas these filter components really need monthly cleaning.

In houses with hot-water or steam heat, as well as attic-mounted, central air conditioning, occupants don’t close off supply diffusers and return grilles in winter, so warm moist house air flows by convection into the ducts in the cold attic, causing condensation that fuels mold growth in the system. This is a particular problem when returns are located in second-floor halls, just outside bathrooms (all those hot showers!).

Clients don’t keep air-to-air heat exchanger units clean. They don’t clean baseboard heating convectors and radiators before the start of the heating season, so potentially allergenic dust becomes airborne when the heat is running.

When central humidification systems are present, they are often the type with water reservoirs. Dust from poorly filtered airflow collects in the reservoirs or on the evaporative pads and serves as nutrient for microbial growth.

When people use portable humidifiers in bedrooms, they can over-humidity, leading to mold and mite problems in carpeting and bedding. Cool-mist humidifiers have water reservoirs and filter pads that collect biodegradable dust and inevitably become overgrown with microbial growth.

People also don’t usually adequately control the relative humidity (RH) below-grade, so conditions are ripe for mold growth.

In unfinished basements with elevated RH, exposed fiberglass insulation can become moldy because the mold is subsisting on dust captured in the fiberglass fibers. That dust can include sawdust if the basement contains a shop, or if construction or renovation occurred in the home, and wood was sawed in the basement.

And mice love to nest in fiberglass, so mouse urine and fecal matter, as well as dead mouse carcasses, can litter the insulation. Talk about unpleasant smells!

A recent study correlated exacerbated asthma symptoms with elevated levels of mouse urine indoors. A mouse infestation is thus a potential health hazard as well as potential odor problem.

I’m sure many of you have seen those rust-colored mouse-urine trails in basements and garages.

Construction professionals share some responsibility in causing IAQ problems. In finished basement rooms, wall-to-wall carpeting captures biodegradable dust. Raised floor platforms can hide moisture and mold problems. Finished walls are often constructed on framing installed next to the damp foundation walls, so the wood (and insulation) facing the walls becomes moldy.

Even a finished ceiling that faces the cold floor can acquire mold growth.

Mold growth can also ensue below grade following a water event. A majority of water-intrusion problems I’ve seen in basements and crawl spaces are due to poor control of roof water at the exterior. How many times have you seen poorly maintained gutters and downspouts? And reverse grading next to the foundation wall?

Now let’s look at the attic, where moldy conditions can exist. Too many of my clients have allowed moist house air to drift up into the attic because their pull-down stairs are leaky, or there are openings in attic ductwork through which air can flow. Then in cold weather, moisture from house air condenses on attic sheathing, leading to mold growth.

Attic mold doesn’t pose the level of exposure threat that basement mold does, but still, if the attic is used for storage, or if there are leaky return ducts up there, exposure can occur.

Attic mold can be a real stumbling block in real estate transactions.

At this point, you are probably thinking that I’m beginning to rant. I’m not just letting off steam; I’m trying to make a reasonable point here, believe it or not. Home and building inspectors can help improve people’s health by offering them some practical advice about home maintenance, or by pointing them to useful resources so they can learn healthy home-maintenance practices on their own.

If you are a home inspector in Massachusetts, you may think that the State’s licensing law lets you “off the hook” when it comes to environmental issues. But people can always sue, and insurance companies often buckle if a settlement might prove less expensive that going to Court (and it usually is the more cost-effective way to go from the insurance company’s point of view).

I was called in as a consultant in a legal case in which a family sued the home inspector because he had not pointed out potential mold problems in the attic of the house he had inspected for them. Several members of the family suffered health symptoms when they moved into the home.

The home inspector’s report stated very clearly that he had been unable to access the attic due to the screwed-on and painted-closed access hatch; but still, the home inspector’s insurance company caved in and agreed to pay to have the entire roof structure replaced. After this work was completed, family members still suffered symptoms. They then claimed that the house was uninhabitable and demanded that the home inspector cover their costs for purchasing the property in the first place.

I was hired by the home inspector’s insurance company. The homeowners wouldn’t give their permission to have me inspect the property, but I read the home inspector’s report, which was detailed and included photographs. I also read the insurance adjuster’s report and several air-quality testing reports that had been done on the property.

It was clear that the basement was crammed with stored goods, and that biodegradable materials were sitting on the slab and leaning up against the foundation walls. In the photographs, I could see visible mold on some of these surfaces. The homeowners were not dehumidifying the basement, so the basement and the occupants’ stored goods were no doubt full of mold growth. And as we know, air in a house flows from bottom to top and out, so moldy basement conditions can have a negative effect on IAQ upstairs.

The mold growing in the attic had been Cladosporium. According to the culturable test results, the mold growing in the basement was Aspergillus, and it was Aspergillus spores that had been found in the house air.

It is fine to use a basement for storage, but the RH must be kept at or below 50% in unfinished space and 60% in finished space. Nothing biodegradable should sit on the slab or be leaning up against cool foundation walls. Rolling metal shelves are best – positioned at least a foot away from the foundation.

I won’t name the location of the property or the names of those involved, in order to protect the innocent – which in this case is just the home inspector, as far as I’m concerned.

The insurance company wimped out by “ponying up” without doing more investigatory work; one company that did the IAQ testing simply reported mold counts and did not discuss possible sources of the mold growth; and the homeowners were responsible for many of the conditions in the house that led to the mold problems in the first place.

Here are 3 tips for home/building inspectors:

First: It’s worth asking your clients if any of them have allergies or asthma. It they do, give them some education on mechanical-equipment maintenance, and on the importance of controlling RH below-grade and roof-water at the exterior. If you don’t want to deal with such issues, include some clear IAQ exclusions in your report form.

Second: If you are ever sued because of environmental issues, do all you can to be sure that the property is adequately inspected by a qualified indoor air quality professional. That doesn’t mean hiring someone who just takes a few air and dust samples and sends them to a lab. It means hiring someone who understands buildings and can identify potential sources of contaminants – someone who will inspect the entire property and not just the area or areas defined as problematic.

Third: Get a second opinion from a seasoned IAQ professional for any indoor air quality report that puts the blame on you.

I’ve been producing these newsletters since 2006, and there are more than 200 people who now receive them. Most of these people are home or building inspectors, but nearly 50 of them are indoor air quality professionals.

I have 3 pieces of advice for that group:

First: Look for the potential sources of IAQ problems, rather than just depending on counts reported by outside labs.

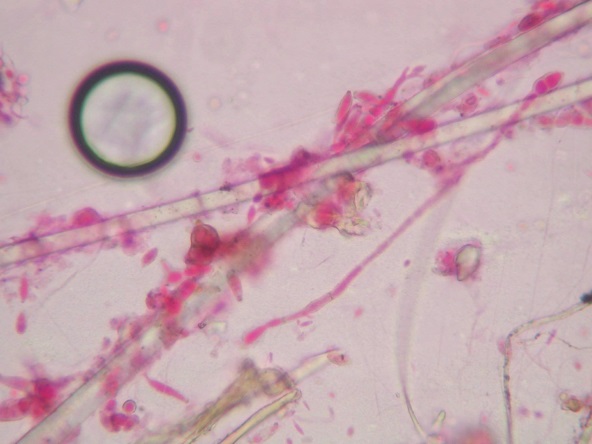

I wish labs would report on whether there are clusters or chains of Pen/Asp spores in samples gathered from an indoor environment, rather than just reporting on counts of spores. Clusters and spore chains of Penicillium and/or Aspergillus mold are a certain indication of indoor mold growth, whereas individual spores could have come from any source, including outdoors. The fact that there may be more spores outdoors than indoors is not that reassuring, if the spores found indoors are in chains or clusters.

Second: If you work for a remediation company, leave air quality testing to some other party. States that have licensing laws for mold assessors and remediators are recognizing that it’s a conflict of interest for one company to do both kinds of work. You potentially face legal exposure by solving a problem that you yourself defined. Protect yourself by relying on a third party to assess the dimensions of the problem.

Third: Last and perhaps most important, learn about buildings. What causes moisture problems? How should mechanical systems be maintained? How can finished basements be constructed and maintained so as to avoid mold problems? What conditions at the exterior of the building can have a negative impact on the building’s indoor air quality?

You can learn a lot about buildings from competent home inspectors, and many members of ASHI (American Society of Home Inspectors) are amenable to taking “ride-a-longs” on their inspections.

Home/building inspectors and indoor air quality professionals have a lot to learn from each other. Let’s get a dialogue going.

Have any questions about indoor air quality?

I’d like to include a “question and answer” section in some of these newsletters.

Send me any question you may have about indoor air quality (jeff@mayindoorair.com). If I choose your question to answer, you will receive a complimentary copy of my book My House is Killing Me.

SOME RESOURCES FOR YOUR CLIENTS: