IAQ IQ Winter, 2016-2017

©2017 Jeffrey C. May

Whenever I attend a meeting with home inspectors or other building professionals, I always enjoy listening to their descriptions of some of the puzzling problems they encountered during their inspections. I learn a lot from hearing these case studies, so I thought I’d share with you some stories from my own investigations.

In this newsletter, I’m going to concentrate on building odors. This is the time of year when I get a lot of calls about such odors, probably because when people shut up their houses for the winter, the odors become more noticeable.

Client #1 owned a condo that had experienced significant ice damming problems the first winter after he moved in. Remediation was undertaken, during which he had spray polyurethane foam (SPF) insulation installed in the attic.

Noxious odors from the foam developed, so he had an attic exhaust fan installed which seemed to prevent the spread of the odor into habitable rooms below the attic. But….

If SPF is not installed under recommended conditions, or if the ingredients are not mixed properly, noxious odors can result. Because of this problem, a number of my clients have instituted legal action – in some cases against the companies that installed the insulation, and in other cases against the developers if the properties were new construction. I worked with one family in Florida who abandoned their new home “lock, stock and barrel” after they experienced health symptoms because of the odor. They left behind their furniture, clothing, and even food in the refrigerator. The last I heard, they had decided to tear the house down.

He called me because an odor problem had developed in his guest bathroom, located on the second floor under the attic. He had already hired a plumber to investigate, as well as an air quality professional to do some testing, but the cause of the odor remained elusive.

When I entered the room, I detected an odor similar to that of bacteria. Sometimes bathroom rugs that are frequently dampened from showering and not dried out quickly enough and/or not washed frequently enough can develop such an odor. He took his bathroom rug out of the room, but the odor remained.

I depressurized the bathroom with a window fan on exhaust, and the odor intensified. I sniffed the airflow from a recessed ceiling fixture and detected the characteristic odor of the amine catalyst in the SPF.

I recommended that he cover the ceiling openings (recessed lights, exhaust fan, etc.) with foil and air out the room as a first simple step. If this reduced the odor, he could confer with a contractor to research his options for sealing these openings altogether. If this did not reduce the odor, however, he had a more complicated problem to deal with.

Unfortunately, such an odor can diffuse through drywall. He could cover the ceiling drywall with aluminum foil (which prevents off-gassing) and then install a new drywall ceiling over that. A more dramatic solution would be to remove the ceiling altogether, paint the foam with shellac, cover it with aluminum foil, and reinstall the ceiling. He would still have to be careful, though, to avoid any unnecessary ceiling penetrations in the room. The most drastic step, of course, would be removal of the insulation.

A “paper towel” test can ascertain whether a surface is off-gassing an odor. Take a piece of clean, odorless paper towel and fold it in half twice. Place the paper towel on the surface to be tested, and cover the towel with a piece of aluminum foil, taped (with blue painter’s tape) at the perimeter to secure the foil and paper in place. Leave this “package” on the surface for 24 to 48 hours. Then remove the package (by folding the foil in half to wrap the paper within the foil), and take it outdoors. Open a corner of the package to reveal the paper towel. Take a cautious sniff of the towel. If the surface has been off-gassing an odor, the paper towel will have absorbed the odor.

Clients #2 (a couple) hired me to identify potential sources of a strong musty odor emanating from their basement. Oh, of course, you are probably thinking – what else but mold? It’s true that the unfinished basement was full of mold growth – not because of a history of water intrusion, but because the space had not been adequately dehumidified.

Many species of mold can grow when the relative humidity or RH is over 80%. Basements are naturally cool and damp, so in the humid season (in New England, usually between mid-October and mid-April), the RH must be kept under 50% in unfinished basements and crawl spaces, and under 60% in finished basements.

The couple was facing a major mold remediation of the basement, as well as professional cleaning of all goods stored there (other than upholstered/cushioned goods, which had to be discarded, along with cardboard boxes and other biodegradable materials that had been on the concrete floor or leaning up against cool foundation walls).

But mold wasn’t the only source of the odor. The basement had exposed fiberglass insulation, and the bulkhead lacked an inner door.

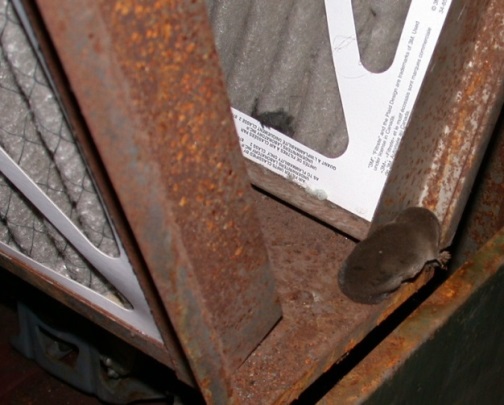

Generations of mice had nested very happily in the fiberglass insulation, leaving droppings, urine, and the dead bodies of their forbearers.

A recent study drew a correlation between increased levels of mouse urine indoors and exacerbated asthma symptoms among occupants.

And shrews, too, had moved in, following one of their favorite prey: mice. Shrews, like skunks, exude an odor that many have described as musty. In addition, they defecate and urinate in big piles that become mold-infested.

In other words, that basement was a horror show!

Even if the couple never went down there, they were breathing air from the basement because of the convective air patterns that take place in a building (hot air rises and exits the upper floor, and air from the lower levels rises up to take the place of the air that leaked out).

As part of the basement remediation in this property, the insulation had to be removed and exposed surfaces cleaned and sealed. Any surfaces that contained mouse droppings or mouse urine stains had to be disinfected as part of the remediation process.

Client #3 was a law firm. An odor had developed in the firm’s conference room – an odor so unpleasant that people were no longer able to use the room. I detected a strong butyric-acid odor; this chemical smells like vomit.

At some point in time, a sponge contaminated with bacterial growth that smelled of butyric acid must have been used to wipe the table. The fix was easy: the surface had to be wiped with a dilute solution of ammonia or baking soda (a base), which would neutralize the acid and thus remove the odor.

Client #4: A couple went away for three months and asked a friend to house sit. The friend stayed in the guest bedroom, which had its own full bath and which had never been used much. When the couple returned, there was a musty odor throughout the home. In preparation for my site visit, I asked that they close the doors to every room. This made it easier to locate the source of the strongest odor, which was in the guest bedroom.

When I opened the guest-bedroom door, I was overwhelmed by the odor, so clearly, here was the source. I sniffed around the bathroom and determined that a half-inch strip of metal on top of the shower threshold connecting the door side of the enclosure to the corner was the ultimate source of the odor. Apparently, there was some biodegradable material under the metal strip that had rarely been wet. In the couple’s absence, the friend must have showered daily and created conditions for the proliferation of stinky microorganisms. Using a hypodermic syringe, I injected bleach under the narrow metal strip. The odor ceased.

Client #5: Here’s another bathroom-odor story. A young man bought his first condo. A few months after he moved in, his guest bathroom developed a terrible musty odor that was so strong, he was embarrassed to have anyone enter the room (kind of an inconvenience for entertaining!).

It’s not unusual to see surface mold growth in a bathroom. People don’t operate the exhaust fan long enough after showering; in addition, an oscillating fan helps move the air and speeds drying of surfaces, but people rarely use such a fan.

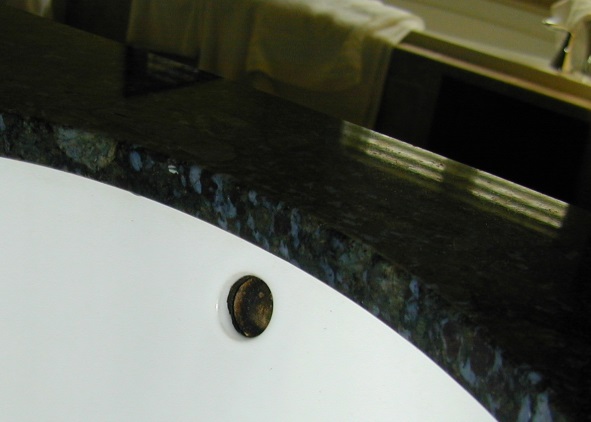

In this case, though, there was no visible mold on the bathroom walls or ceiling. I hadn’t expected there would be, because it was a half-bath. And there were no stains on walls or the ceiling to suggest that pipe leaks may have resulted in mold growth in the ceiling or wall cavities.

The odor source was simple: microbial growth in the sink overflow. All the man had to do was to pour a dilute bleach solution down the overflow, scrub as much of the accessible area of the overflow that he could reach with an old toothbrush, and then rinse the overflow with plain water.

Why should building inspectors care about building odors?

I think there are several reasons why inspectors should pay attention to such problems. First, people are concerned about building odors, so may come back to you with complaints about your work if you did not take note of a discernible odor in your report or while you were at the site. Second, musty odors can be an indication of the presence of mold growth, which is a threat to people with mold allergies. But anyone can become sensitized if exposed to mold for an extended period of time – including you.

Final thought: If you think a building has an odor and you cannot identify the source, recommend further evaluation.

In the next newsletter, I will share some details of case studies of investigations I’ve done of some building-moisture problems. Many of these problems have obvious sources, but some are pretty weird. I’ve also got stories about clients who described problems to me that were hard to believe.

Lots to talk about…

Happy New Year to All